Writing

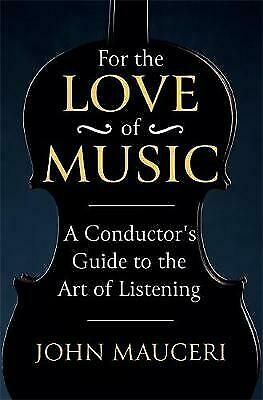

Books about music, invitingly reviewed by a respected musician.

Mark Austin is a conductor, pianist and independent scholar. He is an Associate of the Royal Academy of Music and holds an MPhil in European Literature and Culture from Cambridge University. Full biography here.